| XX |

| XXX |

| XXX |

| Gloria Caruso Murray, 79, Artist and Tenor's Daughter NY Times - December 18, 1999 |

| XXX |

| Enrico Caruso Jr., 82; Actor and Son of Tenor NY Times - April 11, 1987 |

| XXX |

| Note from Ida Sanchez about the Remastering of Caruso's Recordings |

| If you have a picture you'd like us to feature a picture in a future quiz, please email it to us at CFitzp@aol.com. If we use it, you will receive a free analysis of your picture. You will also receive a free Forensic Genealogy CD or a 10% discount towards the purchase of the Forensic Genealogy book. |

| If you enjoy our quizzes, don't forget to order our books! Click here. |

!-- Start Quantcast tag -->

| Quiz #420 Results |

| Answer to Quiz #420 - November 17, 2013 |

| ********** |

|

| ********** |

| Click here for a photo-hint. |

| ********** |

|

|

| Congratulations to Our Winners Janice M. Sellers Arthur Hartwell Marcelle Comeau Nancy Nalle-Mackenzie Sharon M. Levy Rebecca Bare Carol Farrant Cynthia Costigan Sawan Patel Betty Chambers Dennis Brann Suzan Farris Ida Sanchez Elizabeth Olson Edna Cardinal Nelsen Spickard Shirley Yurkewich Dianne Abbot Collier Smith Mike Dalton Elaine C. Hebert Tom Collins Diane Burkett Debbie Johnson Jim Kiser Margaret Paxton Terry Hollenstain Sally Garrison Grace Hertz, Jamey and Mary Turner Team Fletcher! |

| ********** |

| ********** |

| ********** |

| I had already answer the questions, but I had been left with the urge to find the specific recording and the details of it. First thing that came to my mind after knowing by the piece that it was going to be a tenor, was that it did not sound like an early recording. I was actually thinking I would hear Pavarotti, but immediately after Caruso started singing I could tell it had to be him. Finding the answer was very easy, I googled "famous rigoletto recordings" and found it in youtube right away, however, the version I found in youtube did sound like a very early recording, so I knew the one here had been remastered. That led me to 2 questions: when was the original recording made and when was it remastered. As usual, found several misleading sites with it, some claiming 1907 and some 1908. But after being more specific about finding the whole inventory of Caruso's recordings, found the file in the Victor library: victor.library.ucsb.edu/index.php/matrix/detail/200006957/B-6033-La_don na_mobile which says that the recording was made in Candem in march 1908, contrary to what a lot of posters claimed of being in NYC in 1907. One of my google searches insisted me to go to Amazon, which apparently has a collection of all of his recordings (18 years of doing it is a lot!). There, I found this specific one and that led me to an album called "Caruso 2000";, which remastered several of his original recordings. This is the opening song of it. www.amazon.com/Caruso-2000-Enrico/dp/B000031WTO/ref=ntt_mus_dp_dpt_8 |

| ********** |

Enrico Caruso (February 25, 1873 – August 2, 1921)

was an Italian tenor. He sang to great acclaim at the

major opera houses of Europe and the Americas,

appearing in a wide variety of roles from the Italian and

French repertoires that ranged from the lyric to the

dramatic. Caruso also made approximately 290

commercially released recordings from 1902 to 1920. All

of these recordings, which span most of his stage

career, are available today on CDs and as digital

downloads.

Caruso's 1904 recording of "Vesti la giubba" from

Leoncavallo's opera Pagliacci was the first sound

recording to sell a million copies.

was an Italian tenor. He sang to great acclaim at the

major opera houses of Europe and the Americas,

appearing in a wide variety of roles from the Italian and

French repertoires that ranged from the lyric to the

dramatic. Caruso also made approximately 290

commercially released recordings from 1902 to 1920. All

of these recordings, which span most of his stage

career, are available today on CDs and as digital

downloads.

Caruso's 1904 recording of "Vesti la giubba" from

Leoncavallo's opera Pagliacci was the first sound

recording to sell a million copies.

| Enrico Caruso en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enrico_Caruso |

Enrico Caruso was born in Naples in the Via San Giovannello agli Ottocalli 7 on

February 25, 1873. He was the third of seven children and one of only three to survive

infancy. Caruso's father, Marcellino, was a mechanic and foundry worker. Initially,

Marcellino thought his son should adopt the same trade, and at the age of 11, the boy

was apprenticed to a mechanical engineer named Palmieri who constructed public

water fountains. During this period he sang in his church choir, and his voice showed

enough promise for him to contemplate a possible career in music.

Caruso was encouraged in his early musical ambitions by his mother, who died in 1888.

To raise cash for his family, he found work as a street singer in Naples and performed

at cafes and soirees. Aged 18, he used the fees he had earned by singing at an Italian

resort to buy his first pair of new shoes.

At the age of 22, Caruso made his professional stage debut in serious music. The date

was March 15, 1895 at the Teatro Nuovo in Naples. The work in which he appeared

February 25, 1873. He was the third of seven children and one of only three to survive

infancy. Caruso's father, Marcellino, was a mechanic and foundry worker. Initially,

Marcellino thought his son should adopt the same trade, and at the age of 11, the boy

was apprenticed to a mechanical engineer named Palmieri who constructed public

water fountains. During this period he sang in his church choir, and his voice showed

enough promise for him to contemplate a possible career in music.

Caruso was encouraged in his early musical ambitions by his mother, who died in 1888.

To raise cash for his family, he found work as a street singer in Naples and performed

at cafes and soirees. Aged 18, he used the fees he had earned by singing at an Italian

resort to buy his first pair of new shoes.

At the age of 22, Caruso made his professional stage debut in serious music. The date

was March 15, 1895 at the Teatro Nuovo in Naples. The work in which he appeared

| Enrico Caruso Jr., an actor, singer and the last surviving son of the great tenor, died after suffering a heart attack Thursday at his home in Jacksonville, Fla. He was 82 years old. Mr. Caruso was born on Sept. 7, 1904. His mother was the soprano Ada Giachetti. Several years after his father's death in 1921, Mr. Caruso moved to Hollywood, where he starred in two Spanish-language motion pictures, ''The Fortune Teller'' (1934) and ''The Singer of Naples'' (1935). Like his father, he was a tenor. In the late 1930's, he sang regular concerts in California, and made a concert tour of Cuba. After World War II, he gave up singing permanently and, under the name of Henry De Costa, worked as a department head for the import-export firm of Dunnington & Arnold until 1971. At the time of his death, he had just completed a book of memoirs, entitled ''Enrico Caruso, My Father and My Family,'' with Andrew Farkas. He is survived by his wife, Harriett Covington Caruso, of Jacksonville; two sons, Enrico Cesare, of Sacrofonto, Italy, and Wladimiro, of Milan; a half-sister, Gloria Murray of Florida; two grandchildren, and one great-grandson. |

| XXX |

| Gloria Caruso Murray, a visual artist who was the last surviving child of Enrico Caruso, died on Dec. 5 at St. Luke's Hospital in Jacksonville, Fla. She was 79 and had briefly tried to live up to the musical world's sentimental fantasy that she had inherited her father's vocal abilities. She died of cancer, said Aldo Mancusi, curator of the Caruso Museum in Brooklyn. Only hours after his daughter's birth on Dec. 18, 1919, at the Knickerbocker |

was a now-forgotten opera, L'Amico Francesco, by

the amateur composer Domenico Morelli. A string

of further engagements in provincial opera houses

followed, and he received instruction from the

conductor and voice teacher Vincenzo Lombardi

that improved his high notes and polished his style.

During the final few years of the 19th century,

Caruso performed at a succession of theaters

throughout Italy until, in 1900, he was rewarded

with a contract to sing at La Scala in Milan, the

country's premier opera house. His La Scala debut

occurred on December 26 of that year in the part of

Rodolfo in Giacomo Puccini's La bohème with

Arturo Toscanini conducting. Audiences in Monte

Carlo, Warsaw and Buenos Aires also heard Caruso

sing during this pivotal phase of his career and, in

1899–1900, he appeared before the Tsar and the

the amateur composer Domenico Morelli. A string

of further engagements in provincial opera houses

followed, and he received instruction from the

conductor and voice teacher Vincenzo Lombardi

that improved his high notes and polished his style.

During the final few years of the 19th century,

Caruso performed at a succession of theaters

throughout Italy until, in 1900, he was rewarded

with a contract to sing at La Scala in Milan, the

country's premier opera house. His La Scala debut

occurred on December 26 of that year in the part of

Rodolfo in Giacomo Puccini's La bohème with

Arturo Toscanini conducting. Audiences in Monte

Carlo, Warsaw and Buenos Aires also heard Caruso

sing during this pivotal phase of his career and, in

1899–1900, he appeared before the Tsar and the

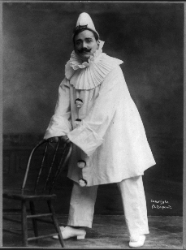

| Caruso as the Duke in Rigoletto |

Russian aristocracy at the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg and the Bolshoi

Theatre in Moscow as part of a touring company of first-class Italian singers.

The first major operatic role that Caruso was given the responsibility of creating was

Loris in Umberto Giordano's Fedora, at the Teatro Lirico, Milan, on November 17,

1898. At that same theater, on November 6, 1902, he would create the role of Maurizio

in Francesco Cilea's Adriana Lecouvreur. (Puccini considered casting the young Caruso

in the role of Cavaradossi in Tosca at its premiere in 1900, but ultimately chose the

older, more established Emilio De Marchi instead.)

Caruso took part in a "grand concert" at La Scala in February 1901 that Toscanini

organised to mark the recent death of Giuseppe Verdi. He embarked on his last series of

La Scala performances in March 1902, creating along the way the principal tenor part

in Germania by Alberto Franchetti.

A month later, he was engaged by the Gramophone & Typewriter Company to make

his first group of acoustic recordings, in a Milan hotel room, for a fee of 100 pounds

sterling. These 10 discs swiftly became best-sellers. Among other things, they helped to

spread 29-year-old Caruso's fame throughout the English-speaking world. The

management of London's Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, signed him for a season

Theatre in Moscow as part of a touring company of first-class Italian singers.

The first major operatic role that Caruso was given the responsibility of creating was

Loris in Umberto Giordano's Fedora, at the Teatro Lirico, Milan, on November 17,

1898. At that same theater, on November 6, 1902, he would create the role of Maurizio

in Francesco Cilea's Adriana Lecouvreur. (Puccini considered casting the young Caruso

in the role of Cavaradossi in Tosca at its premiere in 1900, but ultimately chose the

older, more established Emilio De Marchi instead.)

Caruso took part in a "grand concert" at La Scala in February 1901 that Toscanini

organised to mark the recent death of Giuseppe Verdi. He embarked on his last series of

La Scala performances in March 1902, creating along the way the principal tenor part

in Germania by Alberto Franchetti.

A month later, he was engaged by the Gramophone & Typewriter Company to make

his first group of acoustic recordings, in a Milan hotel room, for a fee of 100 pounds

sterling. These 10 discs swiftly became best-sellers. Among other things, they helped to

spread 29-year-old Caruso's fame throughout the English-speaking world. The

management of London's Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, signed him for a season

of appearances in eight different operas ranging from

Verdi's Aida to Don Giovanni by Mozart. His

successful debut at Covent Garden occurred on May

14, 1902, as the Duke of Mantua in Verdi's Rigoletto.

Covent Garden's highest-paid diva, the Australian

soprano Nellie Melba, partnered him as Gilda. They

would sing together often during the early 1900s. In

her memoirs.

The following year, 1903, Caruso traveled to New

York City to take up a contract with the Metropolitan

Opera. (The gap between his London and New York

engagements was filled by a series of performances

in Italy, Portugal and South America.) Caruso's

debut at the Met was in a new production of

Rigoletto on November 23, 1903. A few months

later, he began a lasting association with the Victor

Verdi's Aida to Don Giovanni by Mozart. His

successful debut at Covent Garden occurred on May

14, 1902, as the Duke of Mantua in Verdi's Rigoletto.

Covent Garden's highest-paid diva, the Australian

soprano Nellie Melba, partnered him as Gilda. They

would sing together often during the early 1900s. In

her memoirs.

The following year, 1903, Caruso traveled to New

York City to take up a contract with the Metropolitan

Opera. (The gap between his London and New York

engagements was filled by a series of performances

in Italy, Portugal and South America.) Caruso's

debut at the Met was in a new production of

Rigoletto on November 23, 1903. A few months

later, he began a lasting association with the Victor

| Caruso in Pagliacci |

Talking-Machine Company. He made his first American discs on February 1, 1904,

having signed a lucrative financial deal with Victor. Thereafter, his recording career ran

in tandem with his Met career, the one bolstering the other, until he died in 1921.

In addition to his regular New York engagements, Caruso gave recitals and operatic

performances in a large number of cities across the United States and sang in Canada.

He also continued to sing widely in Europe, appearing again at Covent Garden in 1904–

07 and 1913–14; and undertaking a UK tour in 1909. Audiences in France, Belgium,

Monaco, Austria, Hungary and Germany heard him, too, prior to the outbreak of World

War I. Caruso's fan base at the Met was not restricted, however, to the wealthy.

Members of America's middle-classes also paid to hear him sing—or buy copies of his

recordings—and he enjoyed a substantial following among New York's 500,000 Italian

immigrants.

From 1916 onwards, Caruso began adding heroic parts such as Samson, John of

Leyden, and Eléazar to his repertoire, while he planned to tackle Otello (the most

having signed a lucrative financial deal with Victor. Thereafter, his recording career ran

in tandem with his Met career, the one bolstering the other, until he died in 1921.

In addition to his regular New York engagements, Caruso gave recitals and operatic

performances in a large number of cities across the United States and sang in Canada.

He also continued to sing widely in Europe, appearing again at Covent Garden in 1904–

07 and 1913–14; and undertaking a UK tour in 1909. Audiences in France, Belgium,

Monaco, Austria, Hungary and Germany heard him, too, prior to the outbreak of World

War I. Caruso's fan base at the Met was not restricted, however, to the wealthy.

Members of America's middle-classes also paid to hear him sing—or buy copies of his

recordings—and he enjoyed a substantial following among New York's 500,000 Italian

immigrants.

From 1916 onwards, Caruso began adding heroic parts such as Samson, John of

Leyden, and Eléazar to his repertoire, while he planned to tackle Otello (the most

demanding role written by Verdi for the tenor voice)

at the Met during 1921.

Caruso toured the South American nations of

Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil in 1917, and two

years later performed in Mexico City. In 1920, he

was paid the then-enormous sum of 10,000 American

dollars a night to sing in Havana, Cuba.

The United States had entered World War I in 1917,

sending troops to Europe. Caruso did extensive

charity work during the conflict, raising money for

war-related patriotic causes by giving concerts and

participating enthusiastically in Liberty Bond drives.

The tenor had shown himself to be a shrewd

businessman since arriving in America. He put a

sizable proportion of his earnings from record

at the Met during 1921.

Caruso toured the South American nations of

Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil in 1917, and two

years later performed in Mexico City. In 1920, he

was paid the then-enormous sum of 10,000 American

dollars a night to sing in Havana, Cuba.

The United States had entered World War I in 1917,

sending troops to Europe. Caruso did extensive

charity work during the conflict, raising money for

war-related patriotic causes by giving concerts and

participating enthusiastically in Liberty Bond drives.

The tenor had shown himself to be a shrewd

businessman since arriving in America. He put a

sizable proportion of his earnings from record

| Caruso with gramophone. |

royalties and singing fees into a range of investments. Biographer Michael Scott writes

that by the end of the war in 1918, Caruso's annual income tax bill amounted to

$154,000.

Dorothy Caruso noted that her husband's health began a distinct downward spiral in late

1920 after returning from a lengthy North American concert tour. In his biography,

Enrico Caruso, Jr. points to an on-stage injury suffered by Caruso as the possible

trigger of his fatal illness. A falling pillar in Samson and Delilah on December 3 had hit

him on the back, over the left kidney (and not on the chest as popularly reported). A

few days before a performance of Pagliacci at the Met (Pierre Key says it was

December 4, the day after the Samson and Delilah injury) he suffered a chill and

developed a cough and a "dull pain in his side". It appeared to be a severe episode of

bronchitis.

During a performance of L'elisir d'amore by Donizetti at the Brooklyn Academy of

Music on December 11, 1920, he suffered a throat haemorrhage and the performance

was canceled at the end of Act 1. Following this incident, a clearly unwell Caruso gave

that by the end of the war in 1918, Caruso's annual income tax bill amounted to

$154,000.

Dorothy Caruso noted that her husband's health began a distinct downward spiral in late

1920 after returning from a lengthy North American concert tour. In his biography,

Enrico Caruso, Jr. points to an on-stage injury suffered by Caruso as the possible

trigger of his fatal illness. A falling pillar in Samson and Delilah on December 3 had hit

him on the back, over the left kidney (and not on the chest as popularly reported). A

few days before a performance of Pagliacci at the Met (Pierre Key says it was

December 4, the day after the Samson and Delilah injury) he suffered a chill and

developed a cough and a "dull pain in his side". It appeared to be a severe episode of

bronchitis.

During a performance of L'elisir d'amore by Donizetti at the Brooklyn Academy of

Music on December 11, 1920, he suffered a throat haemorrhage and the performance

was canceled at the end of Act 1. Following this incident, a clearly unwell Caruso gave

only three more performances at the Met, the final

one being as Eléazar in Halévy's La Juive, on

December 24, 1920.

By Christmas Day, the pain in his side was so

excruciating that he was screaming. Dorothy

summoned the hotel physician, who gave Caruso

some morphine and codeine and called in another

doctor, Evan M. Evans. Evans brought in three

other doctors and Caruso finally received a correct

diagnosis: purulent pleurisy and empyema.

Caruso's health deteriorated further during the new

year. He experienced episodes of intense pain

because of the infection and underwent seven

surgical procedures to drain fluid from his chest

and lungs. He returned to Naples to recuperate

one being as Eléazar in Halévy's La Juive, on

December 24, 1920.

By Christmas Day, the pain in his side was so

excruciating that he was screaming. Dorothy

summoned the hotel physician, who gave Caruso

some morphine and codeine and called in another

doctor, Evan M. Evans. Evans brought in three

other doctors and Caruso finally received a correct

diagnosis: purulent pleurisy and empyema.

Caruso's health deteriorated further during the new

year. He experienced episodes of intense pain

because of the infection and underwent seven

surgical procedures to drain fluid from his chest

and lungs. He returned to Naples to recuperate

| Caruso signing autographs. |

from the most serious of the operations, during which part of a rib had been removed.

According to Dorothy Caruso, he seemed to be recovering, but allowed himself to be

examined by an unhygienic local doctor and his condition worsened dramatically after

that.

The Bastianelli brothers, eminent medical practitioners with a clinic in Rome,

recommended that his left kidney be removed. He was on his way to Rome to see them

but, while staying overnight in the Vesuvio Hotel in Naples, he took an alarming turn for

the worse and was given morphine to help him sleep.

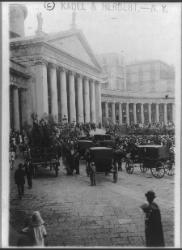

Caruso died at the hotel shortly after 9:00 am local time, on August 2, 1921. He was 48.

The Bastianellis attributed the likely cause of death to peritonitis arising from a burst

subrenal abscess. The King of Italy, Victor Emmanuel III, opened the Royal Basilica of

According to Dorothy Caruso, he seemed to be recovering, but allowed himself to be

examined by an unhygienic local doctor and his condition worsened dramatically after

that.

The Bastianelli brothers, eminent medical practitioners with a clinic in Rome,

recommended that his left kidney be removed. He was on his way to Rome to see them

but, while staying overnight in the Vesuvio Hotel in Naples, he took an alarming turn for

the worse and was given morphine to help him sleep.

Caruso died at the hotel shortly after 9:00 am local time, on August 2, 1921. He was 48.

The Bastianellis attributed the likely cause of death to peritonitis arising from a burst

subrenal abscess. The King of Italy, Victor Emmanuel III, opened the Royal Basilica of

| Hotel just a stone's throw from the old Metropolitan Opera House in New York, Caruso, then the most famous operatic tenor in the world, exuberantly tossed the girl into the air, peered into her mouth and announced, ''Ah, she has the vocal cords, just like her daddy!'' A year and a half later, Caruso was dead at 48 -- a loss that nourished a popular fantasy that his child would also have an extraordinary voice. At age 7, when she and her mother returned to New York from a vacation in Europe, a New York newspaper ran the headline ''Gloria Caruso, Here With a Voice'' and pronounced her ''a potential opera star of the first magnitude.'' The next year she made her first record. At 11, she made her first public appearance, delivering a radio address on behalf of a charity headed by President Herbert Hoover. Later that year she made a test recording for RCA Victor, and John McCormack, another renowned tenor, gave her singing lessons and announced that she had promise. The press had an immense appetite for even the slightest tidbits of news about the great Caruso's daughter. But it gradually became apparent that she did not have the voice to follow her father. In 1942, Ms. Murray told a reporter that she was studying art at the Art Students League in New York and that she had come to prefer the visual arts to music. ''I've always been torn between art and music,'' she said. ''Daddy drew and sculptured as a hobby. And Mommy draws. Art is as much in the family as singing.'' In marrying Caruso, her mother, an American named Dorothy Benjamin, created a tumult in 1918. Her father, Park Benjamin, a wealthy patent lawyer and New York society figure, fiercely opposed the match between his daughter, then 25, to Caruso, who was 45. After the couple eloped, Park Benjamin disowned her. When he died in 1925, he left her $1 from his substantial estate. In 1943, Gloria Caruso married Ensign Michael Hunt Murray, who had left Harvard to become a naval aviator in World War II. The couple had two sons but later divorced. Ms. Murray set up a studio in New York City where she painted both portraits and landscapes. Later she lived in Miami and, for the last 10 years, in Jacksonville. Andrew Farkas, co-author with Enrico Caruso Jr. of ''Enrico Caruso: My Father and My Family'' (Amadeus Press, 1990), said that Ms. Murray's paintings were ''of good quality, although she sold very few.'' ''She became rather reclusive,'' Mr. Farkas said, adding, ''She had been answering questions about her father for a long time.'' Eric D. Murray, one of Ms. Murray's sons, said his mother had become occupied with managing the family estate after her mother died in 1957. Matters were complicated because Caruso had left no will. In 1928, a court in Trenton had ruled that Gloria Caruso was entitled to two-thirds of the royalties on her father's phonograph records, sold by the Victor Talking Machine Company. Gloria Caruso attended Miss Hewitt's Classes in New York City, the Ozanne School in Paris, the Bishop School in La Jolla, Calif., and Miss Nixon's School in Florence, Italy. In addition to her son Eric, of Maryland, she is survived by her other son, Colin D. Murray of Jacksonville. Mr. Farkas wrote that Enrico Caruso had four children from a relationship with Ada Giacchetti, a soprano who had left her husband to live with the tenor before his marriage to Miss Benjamin. Only one, Enrico Caruso Jr., sought a career as a singer. All are deceased. |

the Church of San Francesco di Paola for Caruso's

funeral, which was attended by thousands of people.

His embalmed body was preserved in a glass

sarcophagus at Del Pianto Cemetery in Naples for

mourners to view. In 1929, Dorothy Caruso had his

remains sealed permanently in an ornate stone tomb.

During his lifetime, Caruso received many orders,

decorations, testimonials and other kinds of honors

from monarchs, governments and miscellaneous

cultural bodies of the various nations in which he sang.

He was also the recipient of Italian knighthoods. In

1917, he was elected an honorary member of the Phi

Mu Alpha Sinfonia, the national fraternity for men

involved in music, by the fraternity's Alpha chapter of

the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston.

One unusual award bestowed on him was that of

funeral, which was attended by thousands of people.

His embalmed body was preserved in a glass

sarcophagus at Del Pianto Cemetery in Naples for

mourners to view. In 1929, Dorothy Caruso had his

remains sealed permanently in an ornate stone tomb.

During his lifetime, Caruso received many orders,

decorations, testimonials and other kinds of honors

from monarchs, governments and miscellaneous

cultural bodies of the various nations in which he sang.

He was also the recipient of Italian knighthoods. In

1917, he was elected an honorary member of the Phi

Mu Alpha Sinfonia, the national fraternity for men

involved in music, by the fraternity's Alpha chapter of

the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston.

One unusual award bestowed on him was that of

| Caruso's funeral procession |

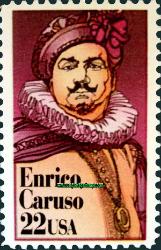

"Honorary Captain of the New York Police Force". Caruso was posthumously awarded

a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1987. On February 27 of that same year,

the United States Postal Service issued a 22-cent postage stamp in his honor. He was

voted into Gramophone Magazine's Hall of Fame in 2012.

a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1987. On February 27 of that same year,

the United States Postal Service issued a 22-cent postage stamp in his honor. He was

voted into Gramophone Magazine's Hall of Fame in 2012.

| Thanks to Sharon Levy for submitting these articles about the first public radio performance starring Enrico Caruso |

TO HEAR OPERA BY WIRELESS Experiment to be made at Metropolitan at "Tosca" performance [sic] New York Times January 9, 1910 WIRELESS MELODY JARRED An Interrupting Somebody Made of It a Ticking Refrain Telling of Beer New York Times January 14, 1910 RADIO ACTIVITY: THE 100TH ANNIVERSARY OF PUBLIC RADIO BROADCASTING Smithsonian Magazine January 26, 2010 |

| XXX |

| ENRICO CARUSO DIES IN NATIVE NAPLES; END CAME SUDDENLY Famous Tenor Succumbs When Taken from Sorrento for New Operation New York Times August 3, 1921 |