| XXXX |

| XXX |

Although the transcription of the melody is unproblematic, there is some disagreement

about the nature of the melodic material itself. There are no modulations, and the

notation is clearly in the diatonic genus, but while it is described on the one hand as

being clearly in the diatonic Iastian tonos, in other places it is said to "fit perfectly"

within Ptolemy's Phrygian tonos since the arrangement of the tones (1 ½ 1 1 1 ½ 1

[ascending]) "is that of the Phrygian species" according to Cleonides. The overall note

series is alternatively described as corresponding "to a segment from the Ionian scale".

Another authority says "The scale employed is the diatonic octave from e to e (in two

sharps). The tonic seems to be a; the cadence is a f♯ e. This piece is … [in] Phrygic

(the D mode) with its tonic in the same relative position as that of the Doric. Yet

another author explains that the difficulty lies in the fact that "the harmoniai had no

finals, dominants, or internal relationships that would establish a hierarchy of tensions

and points of rest, although the mese (“middle note”) may have had a gravitational

function." Although the epitaph's melody is "clearly structured around a single octave,

… the melody emphasizes the mese by position … rather than the mese by function."

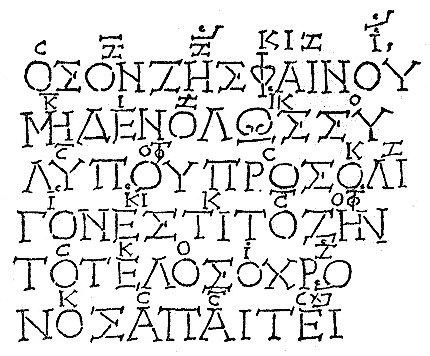

The following is the Greek text (in the later polytonic script; the original is in

majuscule), along with a transliteration of the words which are sung to the melody, and

a somewhat free English translation thereof:

about the nature of the melodic material itself. There are no modulations, and the

notation is clearly in the diatonic genus, but while it is described on the one hand as

being clearly in the diatonic Iastian tonos, in other places it is said to "fit perfectly"

within Ptolemy's Phrygian tonos since the arrangement of the tones (1 ½ 1 1 1 ½ 1

[ascending]) "is that of the Phrygian species" according to Cleonides. The overall note

series is alternatively described as corresponding "to a segment from the Ionian scale".

Another authority says "The scale employed is the diatonic octave from e to e (in two

sharps). The tonic seems to be a; the cadence is a f♯ e. This piece is … [in] Phrygic

(the D mode) with its tonic in the same relative position as that of the Doric. Yet

another author explains that the difficulty lies in the fact that "the harmoniai had no

finals, dominants, or internal relationships that would establish a hierarchy of tensions

and points of rest, although the mese (“middle note”) may have had a gravitational

function." Although the epitaph's melody is "clearly structured around a single octave,

… the melody emphasizes the mese by position … rather than the mese by function."

The following is the Greek text (in the later polytonic script; the original is in

majuscule), along with a transliteration of the words which are sung to the melody, and

a somewhat free English translation thereof:

| XXX |

Fragments of ancient music have been found

going back as far as the eighteenth century B.C.,

the most ancient ones recorded on cuneiform

tablets, but there is only one complete song from

antiquity known to have survived: the Seikilos

epitaph. It was discovered carved on a marble

column-shaped stele in Tralleis, near Ephesus,

Turkey, in 1883, and is now in the National

Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen.

Dating to the first or second century A.D., the

stele announces its function clearly in the

inscription. "Εἰκὼν ἡ λίθος εἰμί.Τίθησί με

Σείκιλος ἔνθα μνήμης ἀθανάτου σῆμα

πολυχρόνιον", (I am a tombstone, an image.

Seikilos placed me here as an everlasting sign of

going back as far as the eighteenth century B.C.,

the most ancient ones recorded on cuneiform

tablets, but there is only one complete song from

antiquity known to have survived: the Seikilos

epitaph. It was discovered carved on a marble

column-shaped stele in Tralleis, near Ephesus,

Turkey, in 1883, and is now in the National

Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen.

Dating to the first or second century A.D., the

stele announces its function clearly in the

inscription. "Εἰκὼν ἡ λίθος εἰμί.Τίθησί με

Σείκιλος ἔνθα μνήμης ἀθανάτου σῆμα

πολυχρόνιον", (I am a tombstone, an image.

Seikilos placed me here as an everlasting sign of

| XXX |

|

| Enter Contest |

| Quiz #462 - January 18, 2015 |

| ********** |

|

| ********** |

| TinEye Alert You can find this photo on TinEye.com, but the quiz will be a lot more fun if you solve the puzzle on your own. |

Congratulations to Our Winners Arthur Hartwell Peter Norton Milene Rawlinson Tom Collins Cynthia Costigan Mike O'Brien Edna Cardinal Karen Petrus Carol Gene Farrant Collier Smith Grace Hertz and Mary Turner The Fabulous Fletchers! |

| If you enjoy our quizzes, don't forget to order our books! Click here. |

-- Start Quantcast tag -->

| ********** |

| ********** |

| If you have a picture you'd like us to feature a picture in a future quiz, please email it to us at CFitzp@aol.com. If we use it, you will receive a free analysis of your picture. You will also receive a free Forensic Genealogy CD or a 10% discount towards the purchase of the Forensic Genealogy book. |

| The Siekilos Epitaph www.mfiles.co.uk/scores/seikilos-epitaph.htm |

| ********** |

|

How Ida Solved the Puzzle |

| XXX |

How Carol Solved the Puzzle |

| Sometimes your questions lead to the answer when Ive drawn a blank on the image. That was the case here. I googled the oldest known and a list of choices came up, one being the oldest known melody. I found myself listening to a lecture about Hurrian Hymn Text H6. While it was in English, I had no clue what the man was saying. I dont speak music. Moving on down the page I came to an image of the Seikilos stele. Bingo! To make sure, I found out more about the stele. Yup, that is it. It is the oldest surviving example of a complete musical composition, including musical notation (aka: doodads), from anywhere in the world. It currently resides at the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen. I do not see how one gets 4 minutes and 30 seconds out of that short little score, but you can listen to it here: www.youtube.com/watch?v=xERitvFYpAk It is quite lovely. As an aside, when reading about Hurrian Hymn Text H6, I couldn't help but think what a pain it must have been to carry around your sheet music. Carol Farrant ***** N.B. I imagine that carrying around sheet music like that would give you a Bach ache. - Q. Gen. |

| ********** |

The "Seikilos Epitaph" is the oldest known

complete song, found with lyrics and music

notation carved on a tombstone in what is

now Turkey. The tombstone and the

significance of its inscription were first

identified in 1883, and is now held at the

National Museum of Denmark. The

engraving and lyrics are in Ancient Greek,

and probably date to the first century AD.

The engraving says "from Seikilos to

Euterpe" and it is thought to be from a man

Seikilos to his wife Euterpe, which is why

the song is known as the "Seikilos Epitaph".

This engraving and other fragments suggest

that the ancient Greeks had used a form of

complete song, found with lyrics and music

notation carved on a tombstone in what is

now Turkey. The tombstone and the

significance of its inscription were first

identified in 1883, and is now held at the

National Museum of Denmark. The

engraving and lyrics are in Ancient Greek,

and probably date to the first century AD.

The engraving says "from Seikilos to

Euterpe" and it is thought to be from a man

Seikilos to his wife Euterpe, which is why

the song is known as the "Seikilos Epitaph".

This engraving and other fragments suggest

that the ancient Greeks had used a form of

music notation since the 3rd or 4th centuries BC. We have not included the Greek lyrics

in this example, but have shown two verses based on the song's melody. The first

verse is played using a harp-like instrument, and the second verse is played on a

recorder or flute-like instrument with the harp (or lyre) strumming chords as an

accompaniment. Despite being 2000 years old, it is surprising how familiar this music

seems. It uses a scale on A in the Mixolydian mode which was common in the musical

theory of Ancient Greece. The music is available as PDF Sheet Music (using modern

musical notation), a MIDI file and an MP3 file.

in this example, but have shown two verses based on the song's melody. The first

verse is played using a harp-like instrument, and the second verse is played on a

recorder or flute-like instrument with the harp (or lyre) strumming chords as an

accompaniment. Despite being 2000 years old, it is surprising how familiar this music

seems. It uses a scale on A in the Mixolydian mode which was common in the musical

theory of Ancient Greece. The music is available as PDF Sheet Music (using modern

musical notation), a MIDI file and an MP3 file.

| Another Example of Ancient Music Hymn to the Moon Goddess, Nikkal, Wife of Yrikh www.phoenicia.org/music.html |

| ********** |

| More about the Seikilos Epitaph www.thehistoryblog.com/archives/27678 |

deathless remembrance".“I am a tombstone, an image. Seikilos placed me here as an

everlasting sign of deathless remembrance.” The last line is damaged, reputedly by

Anglo-Irish railway engineer Edward Purser who was on site building the Smyrna-Aidin

Ottoman Railway when the stele was discovered and who sawed off the base so his

wife could use it as a flower display, but it appears to be a dedication from Seikilos to a

Euterpe, perhaps his wife?

It’s the song that ensured the stele would truly be an everlasting memorial because he

didn’t just have the lyrics engraved, but rather also included the melody in ancient

Greek musical notation. The lyrical message is your basic carpe diem. These are the

lyrics in transliterated Greek and in an English translation:

Hoson zes, phainou

Meden holos su lupou;

Pros oligon esti to zen

To telos ho chronos apaitei

While you live, shine

Have no grief at all;

Life exists only a short while

And time demands its toll

Because of the clear alphabetical notation Seikilos’ song is playable today. Lyre expert

and ancient music researchers Michael Levy has a wonderfully virtuoso performance

on his YouTube channel for which he uses a wide range of lyre techniques to give it

that zesty drinking song vibe.

Musician and Oxford University classicist Armand D’Angour is working on a research

project to use the latest and greatest discoveries on Greek musical notation to bring

ancient music back as accurately as possible.

And now, new revelations about ancient Greek music have emerged from a few dozen

ancient documents inscribed with a vocal notation devised around 450 BC, consisting

of alphabetic letters and signs placed above the vowels of the Greek words.

The Greeks had worked out the mathematical ratios of musical intervals – an octave is

2:1, a fifth 3:2, a fourth 4:3, and so on.

The notation gives an accurate indication of relative pitch: letter A at the top of the

scale, for instance, represents a musical note a fifth higher than N halfway down the

alphabet. Absolute pitch can be worked out from the vocal ranges required to sing the

surviving tunes.

While the documents, found on stone in Greece and papyrus in Egypt, have long been

known to classicists – some were published as early as 1581 – in recent decades they

have been augmented by new finds. Dating from around 300 BC to 300 AD, these

fragments offer us a clearer view than ever before of the music of ancient Greece.

Dr. David Creese, a Classics professor at Newcastle University, has constructed a

zither-like instrument with eight strings on which he plays ancient Greek music. Instead

of strumming or plucking the strings like you would with a lyre or traditional zither, he

strikes them with a little mallet. You can see him playing it in class in this YouTube

video. That is the Song of Seikilos he is playing in that video, incidentally, but obviously

not a full rendition.

Compare Dr. Creese’s version with Mr. Levy’s. I find it fascinating how different the

two performances of such a simple song can be, and it underscores the inherent

challenges of resurrecting ancient music even when you have the words and melody.

everlasting sign of deathless remembrance.” The last line is damaged, reputedly by

Anglo-Irish railway engineer Edward Purser who was on site building the Smyrna-Aidin

Ottoman Railway when the stele was discovered and who sawed off the base so his

wife could use it as a flower display, but it appears to be a dedication from Seikilos to a

Euterpe, perhaps his wife?

It’s the song that ensured the stele would truly be an everlasting memorial because he

didn’t just have the lyrics engraved, but rather also included the melody in ancient

Greek musical notation. The lyrical message is your basic carpe diem. These are the

lyrics in transliterated Greek and in an English translation:

Hoson zes, phainou

Meden holos su lupou;

Pros oligon esti to zen

To telos ho chronos apaitei

While you live, shine

Have no grief at all;

Life exists only a short while

And time demands its toll

Because of the clear alphabetical notation Seikilos’ song is playable today. Lyre expert

and ancient music researchers Michael Levy has a wonderfully virtuoso performance

on his YouTube channel for which he uses a wide range of lyre techniques to give it

that zesty drinking song vibe.

Musician and Oxford University classicist Armand D’Angour is working on a research

project to use the latest and greatest discoveries on Greek musical notation to bring

ancient music back as accurately as possible.

And now, new revelations about ancient Greek music have emerged from a few dozen

ancient documents inscribed with a vocal notation devised around 450 BC, consisting

of alphabetic letters and signs placed above the vowels of the Greek words.

The Greeks had worked out the mathematical ratios of musical intervals – an octave is

2:1, a fifth 3:2, a fourth 4:3, and so on.

The notation gives an accurate indication of relative pitch: letter A at the top of the

scale, for instance, represents a musical note a fifth higher than N halfway down the

alphabet. Absolute pitch can be worked out from the vocal ranges required to sing the

surviving tunes.

While the documents, found on stone in Greece and papyrus in Egypt, have long been

known to classicists – some were published as early as 1581 – in recent decades they

have been augmented by new finds. Dating from around 300 BC to 300 AD, these

fragments offer us a clearer view than ever before of the music of ancient Greece.

Dr. David Creese, a Classics professor at Newcastle University, has constructed a

zither-like instrument with eight strings on which he plays ancient Greek music. Instead

of strumming or plucking the strings like you would with a lyre or traditional zither, he

strikes them with a little mallet. You can see him playing it in class in this YouTube

video. That is the Song of Seikilos he is playing in that video, incidentally, but obviously

not a full rendition.

Compare Dr. Creese’s version with Mr. Levy’s. I find it fascinating how different the

two performances of such a simple song can be, and it underscores the inherent

challenges of resurrecting ancient music even when you have the words and melody.

| ********** |

Above the lyrics (transcribed here in polytonic script) is a line with letters and signs for

the tune:

the tune:

Translated into modern musical notation, the tune is something like this:

|

The Epitaph was discovered in 1883 by Sir W. M.

Ramsay in Tralleis, a small town near Aidin. According

to one source the stele was then lost and rediscovered

in Smyrna in 1922, at about the end of the Greco-

Turkish War of 1919–1922. According to another

source the stele, having first been discovered during

the building of the railway next to Aidin, had first

remained at the possession of the building firm's

director Edward Purser, where Ramsay found and

published about it; in about 1893, as it "was broken at

the bottom, its base was sawn off straight so that it

could stand and serve as a pedestal for Mrs Purser's

flowertops"; this caused the loss of one line of text, i.

e., while the stele would now stand upright, the

grinding had obliterated the last line of the inscription.

Ramsay in Tralleis, a small town near Aidin. According

to one source the stele was then lost and rediscovered

in Smyrna in 1922, at about the end of the Greco-

Turkish War of 1919–1922. According to another

source the stele, having first been discovered during

the building of the railway next to Aidin, had first

remained at the possession of the building firm's

director Edward Purser, where Ramsay found and

published about it; in about 1893, as it "was broken at

the bottom, its base was sawn off straight so that it

could stand and serve as a pedestal for Mrs Purser's

flowertops"; this caused the loss of one line of text, i.

e., while the stele would now stand upright, the

grinding had obliterated the last line of the inscription.

| To hear the melody played with the lyrics, click on the start arrow. |

| The Dedication en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seikilos_epitaph |

| ********** |

The last two surviving words on the tombstone itself are (with the bracketed characters

denoting a partial possible reconstruction of the lacuna or of a possible name

abbreviation)

Σείκιλος Εὐτέρ[πῃ], Seikilos Euter[pei],

meaning "Seikilos to Euterpe"; hence, according to this reconstruction, the tombstone

and the epigrams thereon were possibly dedicated by Seikilos to Euterpe, who was

possibly his wife. Another possible partial reconstruction could be

Σείκιλος Εὐτέρ[που], Seikilos Euter[pou],

meaning "Seikilos of Euterpos", i.e. Seikilos, son of Euterpos

denoting a partial possible reconstruction of the lacuna or of a possible name

abbreviation)

Σείκιλος Εὐτέρ[πῃ], Seikilos Euter[pei],

meaning "Seikilos to Euterpe"; hence, according to this reconstruction, the tombstone

and the epigrams thereon were possibly dedicated by Seikilos to Euterpe, who was

possibly his wife. Another possible partial reconstruction could be

Σείκιλος Εὐτέρ[που], Seikilos Euter[pou],

meaning "Seikilos of Euterpos", i.e. Seikilos, son of Euterpos

| While you live, shine Have no grief at all; Life exists only a short while, and time demands its toll. |

| ********** |

| A More Complete History of the Epitath en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seikilos_epitaph |

| ********** |

| ********** |

| ********** |

The stele next passed to Edward Purser's son-in-law, Mr Young, who kept it in Buca,

Smyrna. It remained there until the defeat of the Greeks, having being taken by the

Dutch Consul for safe keeping during the war; the Consul's son-in-law later brought it

by way of Constantinople and Stockholm to The Hague; it remained therein until 1966,

when it was acquired by the Department of Antiquites of the National Museum of

Denmark (Nationalmuseet), a museum situated at Copenhagen. This is where the stele

has since been located.

Smyrna. It remained there until the defeat of the Greeks, having being taken by the

Dutch Consul for safe keeping during the war; the Consul's son-in-law later brought it

by way of Constantinople and Stockholm to The Hague; it remained therein until 1966,

when it was acquired by the Department of Antiquites of the National Museum of

Denmark (Nationalmuseet), a museum situated at Copenhagen. This is where the stele

has since been located.

| ********** |

| Throughout the excavations of the early 50's archaeologists dug up many fragments of cult songs. Among them were three fragments of a single tablet in different states of preservation. Miraculously, these pieces fit together. As a result, we now have an almost complete text known as the “Song Tablet.” After the tablet was put together, it measured about 7.5 inches long and about 3 inches high. It is inscribed on both sides and even on the edges in wedge-shaped cuneiform characters running from left to right horizontally across the tablet. The text consists of Akkadian terms written in a Hurrianized manner and enscribed in Ugaritic Cuneiform script. The writing on the tablet consists of three parts. First, there are four lines of text that run over, on the front (or obverse, as scholars call it) and continue on the back (or reverse side) covering even the right edge of the tablet. Below this four-line text on the front of the tablet are two finely drawn parallel lines. Between the parallel lines at each end, two angle wedges have been inscribed. Below the two parallel lines is the second part, consisting of six lines. This does not, however, continue on the reverse, although a few signs run over on the right edge of the tablet. A third part is at the bottom of the tablet’s back (reverse) side. To read it, the tablet must be turned upside down. Without even knowing cuneiform, one might guess that this third text is a label which describes the contents of the tablet and which, perhaps, identifies the author or scribe. This label or colophon on the back of the song tablet is written in Akkadian, one of the best known ancient languages. To hear the Hymn to the Moon Goddess Nikkal, click here. |

| Excellent the article on the Siekilos Epitaph on Find-a-Grave www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=88882228 |

| Historic Artifact. An Ancient Greek tombstone dated between 200 BC and 100 AD, it contains the world's oldest piece of music that survives complete. It derives its name from the popular belief that a musician named Seikilos composed the brief song in memory of his wife, Euterpe, and had it inscribed on her grave column. Seikilos probably lived in the historical city of Tralles, now part of Aydin in southern Turkey. He may have descended from a musical family. The stele he erected was of a type commonly used in Grecian culture for those who died young. |

| Its inscription begins: "I am an icon in stone. Seikilos placed me here as an everlasting sign of deathless remembrance". The song follows, an epigram on a theme that is as familiar to us now as it was then: "As long as you live, shine / Let nothing grieve you beyond measure / For your life is short / And time will claim its toll". Epigrammatic verse was also a standard feature on grave columns; what makes the Seikilos Epitaph unique is that he provided the score along with the lyrics, just as epigrams were sung rather than recited in performance. Read more... |